Geopolitical Risk in Latin America: Shock Disruptions, Political Blurring and a Multipolar World

When the heavily-armed Wagner mercenaries advanced most of the way to Moscow, Russia stood on the verge of a civil war. Such events as these in June 2023 serve as a timely reminder that global risks and instability, a feature of this decade, are never far away and are often clouded by uncertainty.

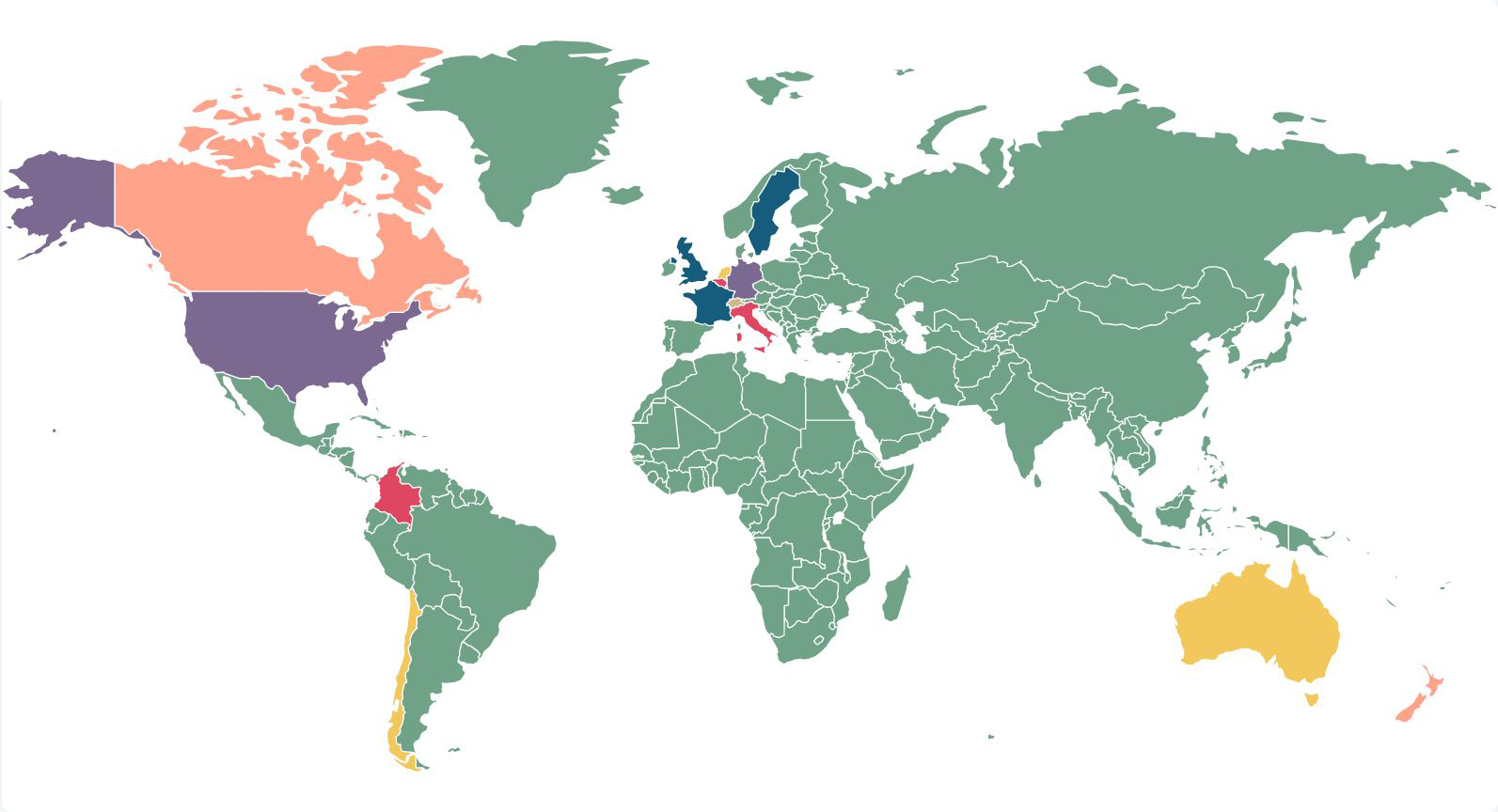

The 2020s have seen a global pandemic, rising inflation, a war returning to the European continent in Ukraine and tensions escalating between the two dominant global powers of China and the US. Our earlier thought leadership on Critical Uncertainties and The Interconnectivity of Solutions has already flagged these systemic risks and how they connect. In this piece, we consider how global risks are converging to impact the emerging markets in Latin America.

David Chmiel, co-founder and Managing Director of Global Torchlight, a geopolitical risk consultancy, says the threat of civil war in Russia gives rise to the greatest threat of all - instability in nuclear weapon possession.

“I think a lot of people would celebrate Putin’s downfall. We need to be careful what we wish for, however, because there is no obvious successor,” he says.

“There is real concern in the US and around the world about who is actually in control of Russia’s nuclear arsenal. It is a very volatile and high-risk situation.”

Disruptions such as the Ukraine war and COVID-19 pandemic, whose impacts can spread rapidly in the globalisation era, have been a defining feature of this decade.

The change from a unipolar world led by the US to a multipolar world, with a more assertive China, is a second characteristic.

Another important shift has been in domestic politics in many of the world’s largest economies: the blurring of left and right-wing policies and the rise of populist leaders.

These three global dynamics - shock disruptions, the shift to a multipolar world, and a political blurring - have been significant for Latin America, a region with a history of political and economic instability.

A multipolar world

China’s influence in Latin America is rising. From 2018 to 2020, China invested an estimated $16bn in overseas mining, with a particular focus on the ‘lithium triangle’, a region across parts of Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile.

Chinese companies have invested heavily as major shareholders in Chilean firms that mine and produce lithium. The mineral is essential for rechargeable batteries in phones, laptops and electric vehicles.

“The relationship between the US and China is the ultimate bilateral friction in our world. It is playing out in Latin America because the region is so resource rich. China is now the largest single sovereign lender into Latin America,” Chmiel says.

“There’s very little understanding of what conditions China is attaching to these loans, but there is a general presumption that it requires countries to agree that China will be paid first in the event of a sovereign default.”

Another dimension of China’s influence in Latin America is growing support for its foreign policy.

In the last six years, Panama, El Salvador and the Dominican Republic have switched their diplomatic allegiance from the Republic of China (which controls Taiwan) to the People’s Republic of China.

There is an ever-present risk of US sanctions impacting companies’ work in Latin America, one that will grow if tensions escalate over Taiwan and the US opts to increase economic pressure on China in response.

Considering China’s investment and foreign policy influence in Latin America, companies should carefully consider their risk mitigation and insurance coverages.

Political risks

Bilateral investment treaties often clarify and enhance the legal rights and obligations applying to investment flows between countries, but companies can still incur losses.

Duncan Strachan, a DAC Beachcroft partner specialising in international disputes and (re)insurance coverage in Latin America and the Caribbean, says: “US sanctions, in particular, can have a long arm effect. While political risk insurance would not cover any loss relating to the breach of international sanctions, it may provide cover for losses resulting from the unilateral decision of a state entity or the nationalisation of assets.”

The risk of nationalisation of assets is potentially on the rise as Latin American voters continue the cycle of electing parties on the extremes of the political spectrum. The nationalisation plans are part of a wider political transformation happening in Chile as both left and right extremes clash. In September 2022, the country rejected a new draft constitution aimed at shifting the market-friendly text to a focus on progressive issues such as social rights, gender parity and the environment. In May, Chile’s far right Republican party secured 22 of the 50 seats on the committee that will rewrite the constitution a second time. They will likely make use of their veto powers.

Adding to the uncertainty, President Gabriel Boric is planning for sectors of the privately-run health and pensions industries to transfer over into state ownership.

Macarena Cambara, a DAC Beachcroft partner based in Santiago who specialises in casualty and financial lines, said: “It’s been very difficult for Chile because inflation rose significantly after the pandemic and it may still rise further.

“We have some instability and division in our politics. We haven’t had an extreme left- wing president for at least 30 or 40 years. On political issues we are polarised.”

The social unrest in Chile in 2019 was aimed at inequality and the cost of living. The protests have underpinned political extremism, as politicians acquiesce to people demanding reforms. Such protests highlight the need for specialist political risk and political violence cover.

Strachan says: “Property damage caused by strikes, riots and civil uprisings were often to be covered in property programmes.

“Although there was a bit of a movement to carve that out of property programmes, there’s now an increased market for specific cover for political violence, which will cover damage caused by those risks.

“It might also cover terrorism and civil war. I believe there’s still plenty of room for growth in this specialist political violence market.”

Liability risks

On the liability side, Cambara notes the rise in people trying to assert their rights through the legal process. Cambara said: “Citizens nowadays are claiming more for their rights through the judicial process. You didn’t see this kind of litigation ten years ago. People used to stay quiet and tried to manage the settlement in private. Nowadays we have claims on environmental liability: for example, a big oil or gas company contaminating the air or polluting the sea, facing a class action from the fishermen and the local people affected.”

Environmental legislation in Chile, and across Latin America, have been on the rise in the last ten years, culminating in the Escazu Agreement which came into force in April 2021. The international treaty signed by 25 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean includes provisions outlining the rights of environmental defenders.

Amid countries developing new environmental laws and regulations, environmental liability insurance has been on the rise. However, the market is still in development and must be approached with caution.

For example, policyholders should understand whether cover is for historic pollution or new events only; whether it covers public land, private land or both.

“It’s important to be very clear with the terms and conditions,” Strachan says. “In general, it’s best practice to be clear and to spell out what the cover does and does not do. This is particularly the case in Latin America because the market there may have a different interpretation of what certain covers, especially the newer types of cover and the bespoke types of cover, are intended to do.”

The other area for claims is directors and officers cover. Across Latin America, there have been numerous and highly-publicised cases of wrongdoing.

In March 2023, Colombia’s comptroller, Carlos Hernan Rodriguez, announced his intention to recover $209m of state resources stolen through organised crime.

In Brazil, Operation Car Wash began in 2014 as a long-running investigation into corruption across large business and politics. It resulted in nearly 280 convictions.

“There’s always a trend for new regimes to criticise what’s happened in the past, or to bill themselves as starting again by tackling corruption. I wouldn’t be surprised to see more investigations against previous governments and public officials and against private companies that were contracting with governments in the past,” Strachan says.

“If I was a director doing business in Latin America on big projects, I would definitely want D&O cover and I would want to make sure that it is broad and sufficient.”

Property risks

As well as these emerging risks, companies should check coverage within their conventional property insurance. This is especially important with climate change and the rising threat of natural catastrophe.

On construction projects, there should be site visits and survey checks organised by insurance companies, especially considering projects can fall into disrepair through state mismanagement, such as the oil industry in Venezuela.

Strachan says: “Sometimes just the standard property cover is overlooked. You should make sure that it is comprehensive - it tends to be on standard forms - and suitable to the insured’s business and location.”

The risks to companies working in Latin America are numerous and unpredictable, but one thing is certain: having the right risk management and insurance coverage in place is as important as it has ever been.