The Tide of Social Unrest in Latin America

The pandemic has kept people off the streets, but only for so long. The success of the protest movement in Chile is encouraging similar activism elsewhere, as seen in Colombia.

When people came out to protest on the streets of Santiago in late 2019, the trigger was as simple as ticket pricing on the city’s metro trains. Over the next six months, an unleashing of pent-up emotion across the country revealed deeper concerns than subway tariffs, particularly economic inequality and dissatisfaction with the political establishment. More than 30 people were killed, and shops and retail businesses bore the brunt of popular frustration in a country not known for social unrest.

Then came COVID-19. The pandemic, plus the government conceding a referendum on rewriting the constitution, helped to keep a lid on Chilean protests. In May 2021, people used the ballot box not their feet to punish the right-leaning government, voting for mostly left-leaning independent candidates to draft a new constitution. Although outcomes remain uncertain in Chile, with another vote needed to ratify a new constitution, democratic processes have, for now, replaced street violence.

In Colombia, the pandemic has played a different part in events, which appear to be headed in the opposite direction. The country has been gripped by unrest since April 2021, when an unpopular attempt to reform taxation was a trigger for widespread anger despite spiking Coronavirus cases.

Like Chile, Colombians’ dissatisfaction with government runs to deeper issues of economic inequality. This, alongside security concerns stemming from terrorism and narcotics, has boiled over from peaceful protests into arson, roadblocks and riots, exacerbated in turn, like in Chile, by some heavy-handed policing.

“Income inequality is the common theme,” says Duncan Strachan, Partner at DAC Beachcroft working in London and Madrid. “We’ve seen simmering discontent boil over and become violent, first in Chile, where things seem calmer for now, then in Colombia, where the situation is ongoing.”

Underwriters traditionally view Colombia as a security hotspot due to its history of narco-terrorism, rather than a civil unrest risk. Mining and energy companies there have habitually bought specialist terrorism covers, but political violence covers are much less common.

“In rural areas, an oil or mining company would historically be exposed to attacks on infrastructure by guerrilla groups. Attacks in cities were much less common,” says Juan Diego Arango, Partner at DAC Beachcroft’s office in Bogota. “Few businesses in cities bought protection against terrorism, and they weren’t focused on protest and social unrest.”

Cali, Colombia’s third-largest city, has been particularly hard hit, with at least 16 people killed and hundreds more injured, as peaceful protests boiled over into roadblocks and riots in urban areas. The government has eased COVID-19 restrictions, in part because so many people have been on the streets despite the pandemic.

“In Bogota, things are open again, despite COVID-19,” says Arango. “The pandemic, and its associated lockdowns and draconian rules – even though they have been a matter of public health – have added to the pressure, resulting in the current civil unrest.”

The pandemic has poured fuel on a potentially incendiary socio-economic situation across the region, according to Thomaz Favaro, a Director at security consultancy Control Risks in Sao Paulo.

“We are seeing an eruption of social unrest in Latin America,” he says. “The pandemic, which has largely kept people indoors amid social distancing, has acted as a pressure cooker for other popular grievances, only increasing the drivers of social unrest.”

Inequality, the economy and corruption

A breakdown in public services during COVID-19 has emphasised issues of inequality. “We’re not talking about deep political issues, but access to public health services and the basic necessities in life, such as prices for food,” says María Jesús Pérez, Associate at DAC Beachcroft’s Chilean practice.

Economic growth has slumped across Latin American economies for several years, after the high growth rates of the 2000s and early 2010s, Favaro underlines. Low commodity prices have badly affected the region’s commodity export driven economies.

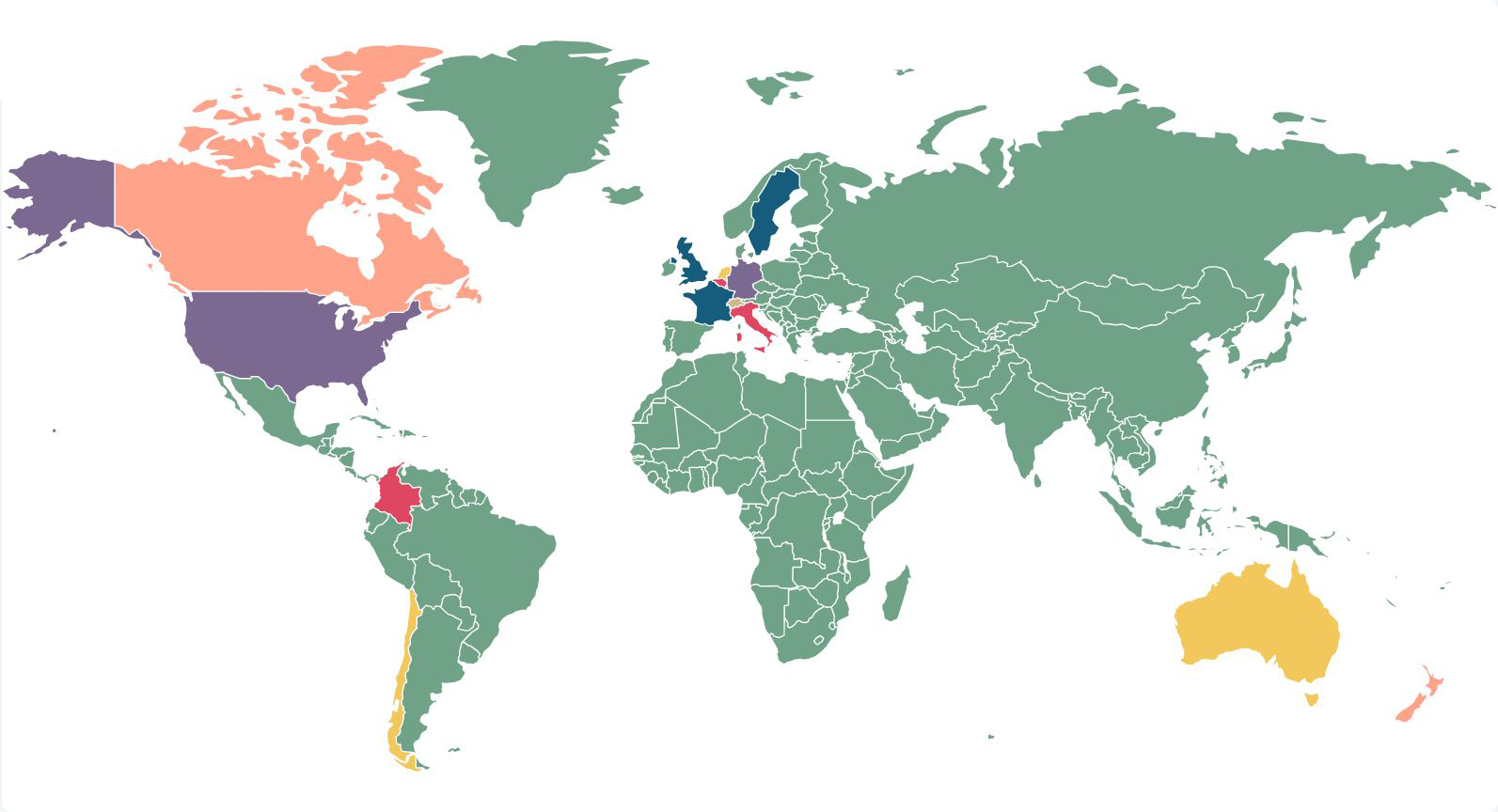

“At the same time, a series of corruption scandals have affected faith in the political establishment across several countries. There was the ‘Car Wash’ scandal in Brazil, and similar bribery and corruption misconduct allegations in Peru, Guatemala and Argentina,” says Favaro. “Political leaders were already failing to deliver growth, instead presiding over budget deficits and unpopular austerity measures. This highly flammable cocktail has led to the social unrest seen in Chile, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador and Colombia.”

Social media

The social media age has also arguably made activists more effective at influencing governments and driving change internationally. Successful activism in one country can influence events in another.

“Protest movements successful in gaining concessions from government will double down on a winning strategy,” Favaro says. “With a new Chilean constitution, people can see how much protestors achieved in a few months, which can lead to copycat effects across borders.”

Pricing and cover

The multi-billion-dollar insurance cost of Chile’s civil unrest is already being baked into the current hard market pricing environment by property insurers and by the international re/insurance carriers that focus on strikes, riots and civil commotion (SRCC) protection, particularly in the hubs of Miami and the London Market.

“The insurance industry had not identified social unrest as a major risk in Chile until after the events of October 2019. Add-ons to property policies, including SRCC protection, were given away as gifts,” says Pérez. “After the events of 2019 things have changed completely. Conditions have tightened to become much stricter, and some prices have doubled to get that additional coverage as a consequence of the huge damage suffered.”

Large multinational retailers were among those making claims. In the case of Walmart, a multinational retail chain, the company faced civil unrest in the US as well as in Chile, and last year the retailer reportedly responded by seeking around $500m in SRCC coverage.

The pricing picture for SRCC is hardened but nuanced across the region. “In the political violence market, unless there is a poor loss record, we’re not seeing rate rises doubling or tripling,” says Christopher Kirby, Head of Political Violence and Terrorism at Optio, a London Market managing agent. “In Colombia, pricing was already relatively high due to long-term terrorism risks, but it’s fair to say that we are seeing rises in territories where the risk environment has deteriorated.”

Low risk retention limits among the region’s local carriers also mean that the bulk of losses for catastrophe events tend to be paid for by reinsurers. There is a focus on what solutions the reinsurance market can provide, with hardened rates reflecting heightened risks.

“You can’t have widespread civil unrest with the pricing on property covers; there simply isn’t the margin to cover those losses,” says Ron Diaz, Executive Vice President at Everest Re, based in Miami, providing reinsurance coverage to Latin American property insurers.

“This is not like an earthquake happening in a particular country with a 72 hours clause; once civil unrest starts it can potentially lead to months of near-continuous rioting and looting. The numbers involved can be unsustainable, so you have to find different ways to cover it,” he continues.

“As a property treaty reinsurer, what we’ve done is to distinguish SRCC risks from main property coverage, working with ceding companies to quantify exposure and price it correctly alongside their other property risks within the treaty. That means smaller SRCC sub-limits, with excesses reset and reviewed accordingly. We’ve seen strong take-up in Chile, and now we’re seeing increased interest in Colombia,” Diaz adds.

Standalone covers are also increasingly in vogue, typically in the form of buying facultative reinsurance, meaning a carrier buys a separate standalone policy for SRCC risks to keep offering its own policyholders consistent coverage. This specialty market for standalone political violence underwriting is an offshoot of the terrorism insurance market.

“Over the last three to four years, we have seen how clients are increasingly buying standalone coverage for SRCC and malicious damage,” says Napoleon Montes-Amaya, Hiscox’s Miami-based Head of Crisis Management.

“This coverage has traditionally been embedded, for the most part, in all-risks policies, however the uptick in political instability in certain territories has led to clients looking for more bespoke coverage provided by specialists,” he says. “From a Latin American standpoint, the SRCC market is both growing and evolving. We are just hitting our adolescence as a market – which was born post 9/11 – and the risk landscape is constantly changing so it’s essential that the industry evolves alongside this to remain relevant.”

Nascent specialist products are also available for risks such as business interruption and events cancellations, which can become consequences of social unrest and government curfews in response to trouble on the streets.

“Protests usually start in urban centres, but their effects can spread to factories and power plants on the outskirts,” Strachan suggests. “Because of demonstrations you could also see business interruption denial of access claims, which may still be covered within property policies.”

Wordings usually come into focus after large loss events, and social unrest is no exception in 2021. While all-risks policies have tightened terms and added exclusions, SRCC carriers are also scrutinising wordings, typically underwritten with US or UK laws in mind.

“In certain jurisdictions, if an exclusion is not written in bold, it’s not enforceable in court,” says Kirby. “We’re increasingly seeing litigation opening up over enforcing a policy written under English law and jurisdiction but a claim is denied because it doesn’t fit the parameters of local policies.”

Additional services – the trusted advisor

One benefit to buyers of purchasing specialist covers can be the services provided in addition to indemnity. Risk advisory or crisis management services form part of this new breed of proactive products for political violence.

“With the world changing at a fast pace, there is an upward trend of clients not just looking for an insurance policy, but for a trusted advisor pre and post loss, should an incident occur,” says Jade Warden, a war, terrorism and political violence Underwriter at Hiscox.

Hiscox partners with Control Risks to provide such services. “This enables us to help our clients to build resilience in their business, respond if an incident takes place, and recover beyond just financial protection,” Warden adds.

Preventative measures for insureds are a related insurance topic in Colombia, notes Arango, with buyers seeking faster pay-outs from insurers for basic pre-emptive measures such as the cost of boarding up windows before violence occurs.

“It’s prudent for businesses to protect themselves, so insureds are asking insurance companies for prevention costs,” he says. “They ask if they can cover those costs to do whatever they need to protect those businesses before something happens or be reimbursed for it afterwards.”

In Colombia, terrorism liability has previously been a factor in favour of preventative action, Arango suggests. “We have had judicial precedents of companies found liable for a terrorist attack, knowing there was a heightened risk of an attack coming and not doing enough to prepare,” Arango says. “That has made these products attractive for insureds, as an insured could also be held liable for damages arising from a riot and civil commotion.”

Insurers naturally want to see preparedness and sound risk management for risk selection as much as insureds want to avoid damage to their own businesses.

“Crucial to companies’ capacity to prepare, respond and show resilience has been their ability to monitor risk,” says Charles Hecker, Partner at Control Risks in London. “Insurers and insureds want to minimise the likelihood of triggering a policy, as well as readiness to minimise the impact of the risk, and the resilience to get back to business as usual.”