Scenario planning is a key tool that can tease out the answers (see boxes: Scenario planning- the concept and Scenario planning – the basics). Its unique feature is that it forces us to contemplate highly disruptive uncertainties and start to plan for them and, in doing so, pro-actively build genuine operational and financial resilience, not just a back-up plan to keep the proverbial lights on. If the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us anything it is that we shy away from this challenge at our peril. As The Economist recently reminded us in a leading editorial entitled “The next catastrophe” (27 June 2020):

“Scanning the future for risks and taking proper note of what you see is a marker of prudent maturity. It is also a salutary expansion of the imagination”.

Scenario planning - the concept

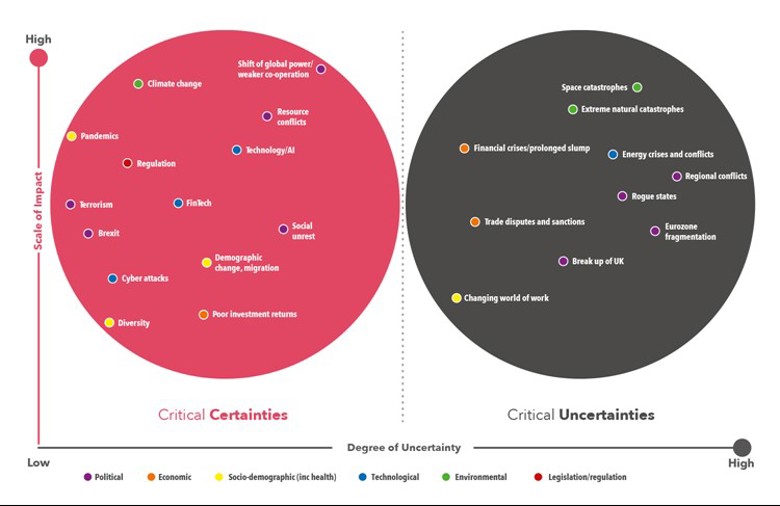

A key objective of scenario planning is to separate critical certainties from critical uncertainties, the latter tending to be those overlooked by conventional horizon scanning studies. One of the reasons is that, by their nature, they do not lend themselves to modelling because there is little or no data to input into models. They therefore require a qualitative approach, including deterministic quantification, to analyse their impact and the implications for building operational resilience. It is important not to be lulled into a false sense of security by the language of this approach to scenario planning. Certainties present challenges too: the crucial word is critical.

Critical certainties are those events where we know something will happen that will be disruptive and which businesses must take into account in their business strategy and operational planning. It might not, at this stage, always be clear precisely what those impacts might be. Brexit is an obvious example, as is climate change. The development of artificial intelligence is another that has found a place as a critical certainty on most boardroom agendas in recent years .

Critical uncertainties are those events that might happen and if they do could be very disruptive. Some hover between the two: the break-up of the UK might be considered one of those. Others are potentially beyond those boundaries of what conventional insurance can respond to. Unless we understand those risks we cannot define those boundaries.

Scenario planning - the basics

Scenario planning is very different to business planning. It runs alongside established planning processes, but is different in at least five key ways.

- Scenarios focus on uncertainties – issues that we do not fully understand. Traditional planning focuses on certainties – the known, predictable and, usually, measurable.

- Scenarios explore extremities, outside conventional ways of thinking about insurance, commerce and the world.

- Scenarios examine multiple futures, typically between two to four, not just one. This is key as it encourages positive thinking about the future.

- Scenarios describe the future in qualitative, not quantitative terms. Some scenarios will have the benefit of quantitative projections but these should not be used to introduce a feeling of certainty, when, in reality, none exists.

- Scenarios typically look further ahead than business plans. Five years would be a minimum but ten to 20 years is more typical.

Businesses need imagination when it comes to looking for risks that pose an existential threat to themselves and their clients. Once pulled far beyond the boundaries of corporate comfort zones, they can quickly place things in the “Too Hard” tray to be contemplated on another day, which often never comes. At least, not until it is too late.

For example, pandemics have been on the UK’s national risk register and the emerging risks log for many insurance businesses for several years. The emerging risks log is clearly the wrong place for this risk, rather companies should have developed stress tested scenarios to understand the financial and operational impacts a pandemic could have on their business and risk portfolio.

Scenario planning is not all about searching for negative impacts. Many uncertainties are wrapped around opportunities, for instance the rapid development and deployment of artificial intelligence. Even those that appear initially to be very negative may contain the seeds of progress. Over many generations war has been a great driver of medical, scientific and technological progress. Huge advances were made in plastic surgery when treating the horrific facial burns of fighter pilots, and the work of the codebreakers at Bletchley Park progressed computer science significantly. The pandemic too has accelerated the adoption of video conferencing, mobile working and home schooling, although this has then introduced increased vulnerability to cyber risks.

The insurance industry has a critical role to play in helping the world build resilience in the face of severe risks as it fulfils its primary role of allowing policyholders to transfer risks off their balance sheets. It also needs to map the responses, consequences and cumulative effects as well as track new risks that merge in the wake of rapid change.

The bigger picture

In many markets, the pandemic has forced the relationship between insurers and their clients uncomfortably into the spotlight as it has exposed a gulf in understanding and expectations, including over policy wordings on business interruption. Already, this is prompting braver firms to look beyond COVID-19.

“Insurers are looking at the pandemic and trying to work out what might hit them next. They want to know what the next big disruptor might be and how it might impact them”, says Helen Faulkner, Head of Insurance at DAC Beachcroft.

The immediate concern is to understand how critical uncertainties might hit existing business: “We are seeing interest in reviewing policy wordings across all classes of business. Insurers are looking at the impact of big events such as social unrest, external power surges, nuclear or war events, extreme natural catastrophes and so on. Cyber risks were already acting as a wake-up call and the market is looking at affirmative language but the pandemic has raised awareness of potential vulnerabilities in wordings to a new level”.

This is a start but more is needed. This essentially operational response needs to be placed in a much wider context, argues former Conservative cabinet minister Lord Hunt of Wirral, DAC Beachcroft Partner and Chairman of the Financial Services Division.

“The events of 2020 should make us very cautious about treating anything as certain. Just a year ago we all had certain working assumptions which now seem pretty shaky, particularly around economic growth, rising life expectancy and political stability in the developed world.

“There has been a general failure to anticipate the full extent of the damage a pandemic on this scale can cause. Serious thought now needs to be given to what can reasonably be privately insured and what cannot”.

“These are huge questions and huge challenges”, he adds.

The potential growing role of the state in the insurance market is one of the threads that links many of the critical challenges the insurance market faces. It is already on the UK government’s agenda. In March this year the Treasury issued a paper entitled Government as Insurer of Last Resort in which it set out a framework for extending the state’s current role in underpinning the insurance market:

“… there can be a missing market for insurance against high impact, low probability events. The government can ensure that this risk is covered by taking on the large tail-end risk of an extremely unlikely but catastrophic event”.

That framework is now likely to be tested. The vast sums committed to job retention schemes and business grants are also tantamount to providing a social insurance backstop targeted at the most economically vulnerable.

This is a debate the insurance industry should lead says Charles Clarke, Home Secretary in Tony Blair’s government.

“What is the role of government as insurer of last resort? What is the role of government as a builder of resilience? What is the role of corporations and other organisations in terms of building their own resilience?”

“Working out liabilities is very difficult for these big risks and raises philosophical questions about the role insurance plays.

“Its social utility is that it does provide resilience to society but then there are some major challenges when you say we are not going to provide resilience for a whole series of risks which could well happen. Then insurers begin to lose their legitimacy. That is why insurers must lead the discussion about solutions”, says Clarke.

This is also about engaging business leaders. As stewards of a company, directors must take responsibility for ensuring it has appropriate plans in place for significant disruptions. This is closely aligned with the Bank of England’s approach to resilience.

Reputation

Trust must be at the heart of the insurer/client relationship and this has been tested by the pandemic. Reputation is a thread that weaves its way through the maze of critical certainties and critical uncertainties.

Where are the boundaries of what the commercial insurance market can reasonably cover? The answer to that question lies in an honest assessment of the critical uncertainties that the world faces and for which society will need to develop much greater resilience to mitigate the potential shocks.

Fig 1: Mapping critical certainties and uncertainties

Mapping some of the major issues facing insurers over the next decade. Those that fall on the certainties side should already be embedded in operational and financial resilience. Those scenario planning issues placed on the uncertainties side are often overlooked or not fully assessed for their potential impact. They should be taken seriously.

Click to enlarge

Critical certainties and uncertainties

The pandemic is a grim reminder of what happens when we limit our imagination when looking for potentially catastrophic events, sometimes labelled black swan events. As a word, “pandemic” has been bandied around in health and government circles for many years but few engaged in active discussion about what it really meant. The varying responses of governments around the world is perhaps revealing of those countries where the discussion did enter the mainstream and where resilience was greater as a result.

It would be harsh to condemn the insurance industry for ignoring the threat of a pandemic entirely. Papers and articles have been published over the years. In 2013, a team from Aon Benfield published a paper in The Actuary which stated the challenge in unequivocal terms: “… pandemic risk remains the most important mortality exposure for the insurance industry and is placed above other forms of catastrophic event including natural catastrophes, nuclear explosions, and terrorism”.

It examined the mitigation and response measures recommended by the World Health Organisation, many of which we are now experiencing such as school closures, curtailment of domestic and international travel and community tracing, but bemoaned the failure of the catastrophe models used by insurers to address these. A black swan overlooked, if not ignored.

Our focus on the risks associated with pandemics has taken the spotlight off the enormous and varied threats posed by climate change, but all these risks must all now be taken much more seriously says Faulkner.

“Extreme natural catastrophes are very concerning. Their impact is growing in severity all the time. There are also a lot of potential triggers for destabilising conflicts with any number of localised conflicts that could get out of hand. The potential for energy crises to cause conflict is very real. These are often difficult issues. We should not be scared to discuss these issues, get involved and be at the forefront of discussing responses and solutions.”

Alongside the challenges of modelling risks lacking broad and deep data, another barrier is sensitivity, especially when it comes to mapping major geo-political risks. These loom large in our world today. Stories of growing tensions between the West and China are in the headlines on a daily basis. Where could this end? War by the proxy of international trade could fracture complex supply chains, another of those threads that runs through many of the critical uncertainties. Could firms be faced with a stark choice of doing business with China or doing business with Trump’s America? If the proxy war escalates and disputes over China’s territorial claims move into a more active phase, how prepared are firms with major business links in the Far East for military conflict in the South China Sea?

Major natural catastrophes are similarly almost too frightening to contemplate.

The world is overdue a major volcanic eruption – perhaps Yellowstone. Scoping out the potential fallout from such an event is chilling. Not only would there be the obvious loss of life, widespread property damage, the huge disruption to air travel and the threat to the health of tens of millions of people affected by the fallout but the prospect of years of crop failure and subsequent food shortages. What does resilience in the face of that threat look like?

Space provides more than its fair share of unquantifiable risks, such as solar flares or coronal mass ejection. The last such event – the Carrington Event – happened in 1859, when the world was only on the cusp of relying on technology. A repeat, which say scientists, could come with very little warning and disable electricity grids, satellites, GPS and communications, including those systems that provide early warnings of missile attacks. It could take years to restore reliable electricity supplies in many unprepared countries.

Space holds other critical uncertainties as the recent satellite-to-satellite missile tests carried out by the Russians reminded the world.

Other issues straddle the dynamic split between critical certainties and critical uncertainties, for instance the potential break-up of the United Kingdom. For many people the trigger could be Brexit but it could also be fuelled by public perceptions of how COVID-19 has been handled, says Clarke:

“The fundamental issue is people’s overall confidence in the quality and competence of the UK government and that is the sense in which COVID-19 has been a challenge. However, it is recoverable”.

Climate change is another major issue that might find a home on both sides of this divide. Almost every business – and certainly all major insurers and brokers – has climate change as an issue core to their business and to their clients. Like pandemics and many of the other critical certainties it also exhibits the characteristic of being drawn out over time. But there is another dimension to climate change and that is the increased likelihood of extreme weather events, one-off catastrophes. Where analysis of the threats from climate change falls short for so many brokers and carriers is their failure to analyse the consequences of the various components of climate change, such as rising sea levels, warmer temperatures, water shortages and wildfires.

There is a judgement to be made as to whether these extreme events count as critical uncertainties: perhaps we are now in an era where there is now hard scientific evidence that these events are certain to happen, although it is still hard to predict when and to what extent.

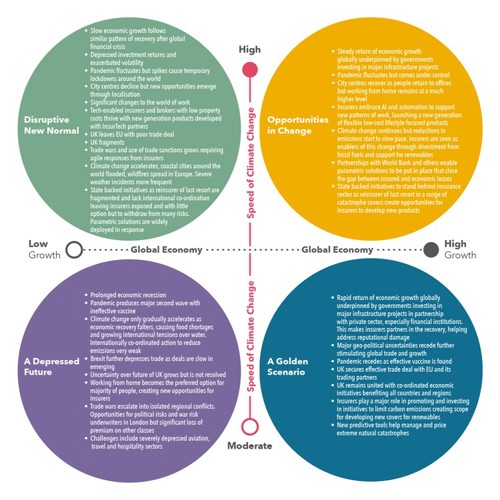

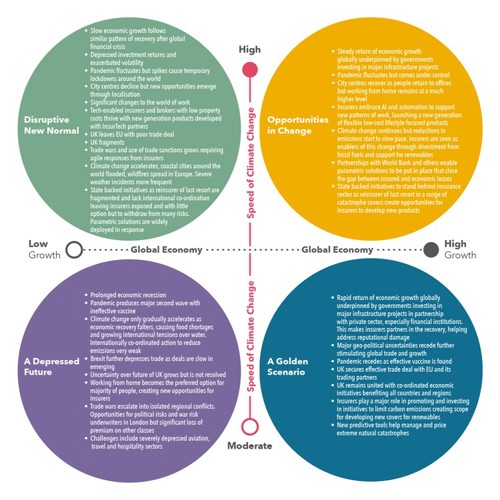

Fig 2: How super uncertainties interact

Many of the issues can be grouped into two ‘super uncertainties’ to better assess the potential impact on the insurance sector. Here we map the impact of the global economy against climate change, as most likely to be the two biggest drivers of uncertainty over the next decade.

Click to enlarge

What can we do now?

Without doubt critical uncertainties look intimidating and it is easy to see why businesses – and governments – often find them too hard to address. They do not have to be.

The objective of scenario planning is to develop a dynamic matrix that maps both the critical certainties and critical uncertainties bringing out the threats and the opportunities (see Fig 1 above). This needs to include considering the consequences and cumulative effect of any action taken. Those that find themselves on the far left of the certainties matrix are the issues that should already be part of day-to-day business planning, strategy and delivery. As you move across the matrix the issues are surrounded with a higher degree of uncertainty and eventually cross-over into the world of critical uncertainties. Once there, it is those that migrate to the top right hand corner – extreme uncertainty and high impact – that should attract the most attention.

It is often helpful to categorise each risk as they are plotted. This will highlight the sort of knowledge and expertise you might need to access in order to understand the issue better and also where it might sit within the broader business planning of a firm. The matrix used here categorises them as P.E.S.T.E.L.

- Political

- Economic

- Socio-demographic (including medical)

- Technological

- Environmental

- Legislative (including regulation)

This will help plot them into a further matrix that groups them to create broad, plausible scenarios that bring together the potential positive and negative impacts of all the certainties and uncertainties that have been mapped using the other approaches. Companies should also cross-reference these uncertainties to the Business as Usual (BaU) risks in their risk registers and should be challenging risk management functions to identify the risks documented in the risk register or emerging risks log that have the potential to be severely disruptive.