The cyber class of insurance is young, high-growth and exciting. And just as cyber market participants are less mature in years, so is the class of business they are underwriting and distributing.

The modelling of cyber insurance is also in its infancy. At the same time our reliance on systems is only increasing, with a move to the cloud accelerated by the global COVID-19 pandemic.

We are also yet to define conclusively where coverage lies. When a major loss scenario comes to pass will the final definition of loss meet client expectations?

And if it doesn’t what are the most likely disputes and reputational issues for the industry that could arise?

Let’s first get a feel for the numbers we are dealing with.

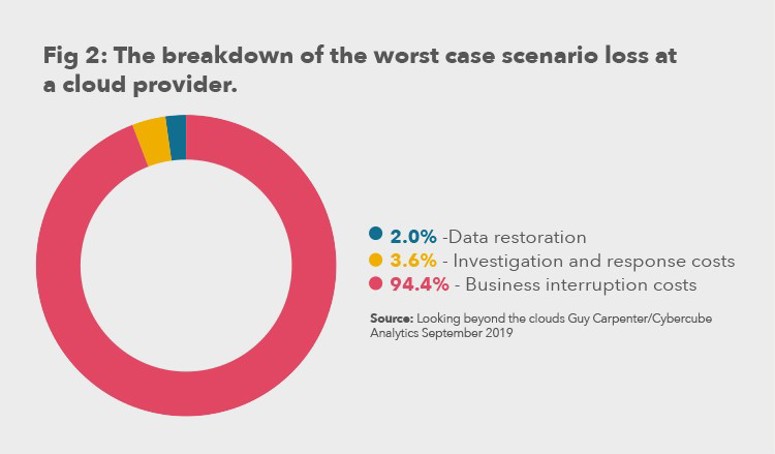

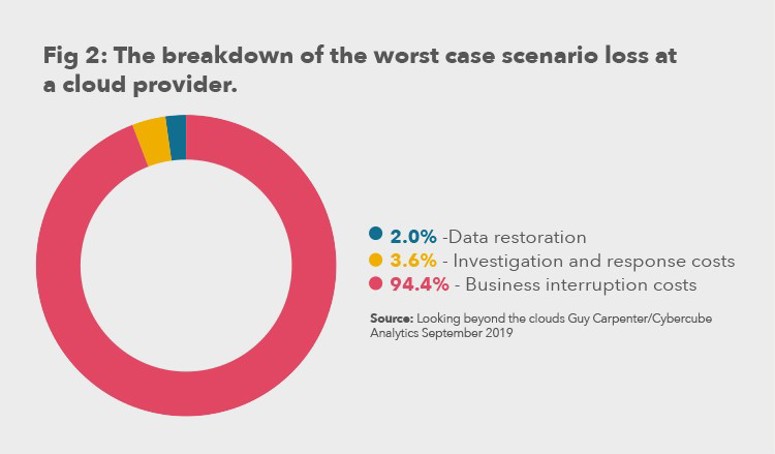

A September 2019 study co-authored by reinsurance broker Guy Carpenter and cyber modelling specialist CyberCube Analytics entitled Looking beyond the clouds ran some numbers for the US industry.

Using a $2.6bn gross written premium base the study found that a 1-in-100 year return period produced total annual cyber catastrophe insured losses of $14.6bn (see fig. 1).

This figure could include one or more events within the same year. The 1-in-200 year industry event was only slightly more impactful at $16.1bn. At 92%, the vast majority share of the losses came from business interruption (see fig 2).

Extreme worst-case single loss scenarios at much lower probabilities ranged from an insurance bill of $11.5bn from a large-scale cloud ransomware at a leading cloud services provider to a widespread data loss from failures in a leading operating system, causing a $23.8bn insured loss at a 300-plus year return period.

For mature markets the modelled losses do not appear to be hugely out of kilter with the base premium and the current industry income should be able to fund its cat costs. This may not be the case everywhere.

“Even though it is in its infancy, the challenge with modelling is whether it will ever be effective. You can underwrite and model for adequate systems and processes, however this is not an indiscriminate risk like the weather. We are seeing targets handpicked across all manner of industry sectors in circumstances where the risk profile can change overnight as new vulnerabilities are exploited and attack vectors shift”, says Kieran Doyle, Partner with Wotton + Kearney in Sydney.

“While overseas markets are becoming more mature, the Australian cyber market is still in its infancy meaning that a few significant losses in a single year would likely threaten the Australian market’s entire premium pool”, warns Doyle.

Mismatch 1: War or no war?

But in the real world would this represent the true picture? How many of these billions would be in dispute? How might war exclusions come into play?

As Oliver Brew, Head of Client Services at CyberCube explains, a huge question mark still arises over coverage for acts of war:

“We chose to park the hotly contentious debate as to whether a cyber war exclusion may impact the recoverable losses… Attribution for cyber events is notoriously difficult either because of obfuscation by the protagonists, or simply the threshold between a kind of malicious cyber event and what is then categorised as an event of cyber war.”

Hans Allnutt, Partner and Head of Cyber and Data Risk at DAC Beachcroft in London backs up the view: “There is not so much a gap, but there is a lack of certainty as to whether cyber activities amount to war” he explains.

In America, there is a keen debate around the extent that the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act (TRIA) extends to possible state-sponsored cyber attacks.

“There are still a number of unanswered questions concerning TRIA, and the US Government Accountability Office has been directed by Congress to address these issues. As noted by the American Academy of Actuaries, given the nature of cyber attacks, it is often difficult to pinpoint the exact source, timing and motivation of threat actors. As such, there is a strong desire for specific guidance as to which types of attacks are considered terrorism, and the relevance of the involvement of foreign governments in determining whether an act is considered terrorism or ‘war’ for purposes of coverage under TRIA,” says Anjai Das, Partner with Wilson Elser in Chicago.

This is far from an exclusively UK or US problem, says Dr Franz König, Partner at BLD Bach Langheid Dallmayr in Cologne.

“War is used in the context of inter-state conflicts in many German insurance contracts. So, it is totally unclear what a ‘cyber war’ is. The criteria used for traditional warfare is insufficient. ‘Cyber-terrorism’ faces the same problems. We need to form new, cyber-oriented exclusions for these phenomena.”

Graeme Newman, Chief Innovation Officer at leading cyber managing general agent CFC Underwriting, is clear that war exclusions are written into all policies.

The war exclusion is a very broad one. Newman says that if there was a event and a nation state was looking to cause mass destruction through cyber, this would be a loss “that market could not bear”.

The only solution would be state-backed schemes in the mould of the UK’s Pool Re terrorism , added Newman.

However, Newman explains that in marked contrast to overt war, the market is prepared to give coverage to such difficult-to-prove war-like acts.

“The real problem is criminal gangs operating with state sponsorship and committing large mass malware campaigns – this is covered by the market right now and seemingly there is appetite from within the reinsurance market to give ongoing coverage for that.”

However dispute-hunters can readily appreciate that if the act were systemic and damaging enough, the temptation or the necessity to litigate the war exclusion is there for all to .

Mismatch 2: Broad utilities exclusions

It is not uncommon for cyber insurance policies to include major systemic risk exclusions inserted by their cyber insurer. Events such as power utilities going offline or a catastrophic failure of the internet and satellite communications systems are not covered.

The loss potential from all these scenarios is vast. Equally huge is the potential for the insurance industry to find itself in a reputational position similar to during the global COVID-19 pandemic over business interruption cover for small businesses.

“Imagine those big, big systemic events. They are largely excluded and that might be another area where customers would have a shock when that event happens,” Newman explains.

“That’s likely to be the big dispute and one that can only be solved with some kind of specialist backstop solution.”

Hans Allnutt agrees and adds a strong observation about the increasingly ubiquitous cloud providers such as Amazon Web Services:

“Cloud providers are effectively becoming a utility so you could say ‘what happens if the internet goes down?’ but the insurers will typically exclude utilities such as electricity for that reason.

“Cloud providers are in that grey zone of almost becoming a utility – potentially uninsurable, but from a policyholder perspective that’s the sort of thing you want cover for.”

Currently a competitive market makes excluding exposure to big cloud providers impossible, but grey zones abound. Some markets are working towards new exclusions but the solutions are far from clear, says König.

“In some new cyber wordings special exclusions were placed for ‘business interruption as a consequence of loss of service by a cloud-service-provider’. But that’s not market standard and there are no specialised clauses with regard to big systemic events.”

Any failure to grasp the implications of how greater reliance on cloud services and the complex interdependencies could cost insurers dear, warns Ian Stewart, Partner with Wilson Elser in Los Angeles.

“The coronavirus pandemic has caused businesses in almost every industry sector to greatly increase their reliance on technology and infrastructure. This dependence on technology has resulted in an increased operational risk alongside insurance cover that has often not kept pace. Network systems have problems and computers fail. Though most companies can find adequate cyber coverage for routine systems failures, growing reliance on cloud service providers is making it more difficult to determine whether an occurrence is an insurable failure of the insured’s computer system or an uninsurable infrastructure failure. Unless the insurance market begins to adjust to this new reality, carriers may find themselves on the wrong end of future US court judgments.”

Mismatch 3: Small managed service providers and outsized blow-out losses

The third mismatch comes in the form of a genuine underwriting shock which may catch many carriers unaware.

A very big and potentially unexpected loss occurs like this:

While underwriters are busy worrying about a major outage at a mega Amazon, Microsoft or Google cloud platform, hackers are busy worming their way into much smaller managed service providers (MSPs).

Perhaps it is a payroll or accounts provider or a niche player that has specialist services tailored to a particular sector.

It may be relatively small in the grand scheme of things but it might have tens of thousands of customers. If a hack destroyed data at 10,000 of its clients, at $1m apiece that is a $10bn single risk loss. And quite possibly that one loss could be with a single insurer, exceeding its reinsurance protections and possibly imperilling the carrier itself.

Newman points out that such losses are wholly plausible and indeed likely to be relatively frequent: “If I were in Lloyd’s that would be the event I would be more worried about… Put your return period on that, but I tell you it’s not 1-in-250, that’s for sure."

Allnutt cites the recent example of a ransomware attack at service provider Blackbaud. This firm had cornered the market in supplying cloud based services to not-for-profits and education, managing assets like donor and alumni databases for notable universities and charities.

“This one attack on Blackbaud has trickled down into hundreds of notifications and claims,” Allnutt advises.

Luckily it appears data was not destroyed in the Blackbaud case, so most of the loss will centre on breach notification expenses, but the warning signs for the industry are clearly there (see Box below).

A shock loss leading to insolvency can only mean lots of litigation.

Small MSPs face myriad challenges

Smaller MSPs present a serious vulnerability for a wide range of businesses and for their insurers.

“Multiparty breaches are becoming increasingly common in Australia where an unexpected attack on a smaller service provider has significant consequences for downstream customers. In particular, we are starting to see an increasing trend in third party business interruption claims commenced by customers, along with the significant migraine that comes with having to field persistent update requests from B2B customers. In these claims, communication strategy is vitally important and for a smaller service provider, they can quickly be overwhelmed with questions from customers that are often significantly larger than themselves,” says Kieran Doyle.

“Even if the MSP’s customers impacted by the event have their own cyber insurance, it is not unusual for the customers (and their own cyber insurers) to make demands on the MSP for reimbursement and indemnification of any and all amounts and losses incurred by the customers in response to the incident. These amounts may include legal expenses, notification costs, reputational harm, and business interruption costs. As a result, a single MSP incident can rapidly turn into an aggregate loss situation complicated by insurance coverage disputes and subrogation rights of insurers and insureds alike. This problem is intensified if a cyber carrier insures both the MSP and its customers,” says Anjali Das.

Mismatch 4: Privacy – a new exclusion?

One last possible mismatch is the increasingly vexed area of privacy.

Hans Allnutt explains that cyber insurance has always historically been sold as cyber and privacy insurance.

As major economies have regulated and new rules such as GDPR have developed, claims over the way data handlers behave and customer data is exploited have also begun to develop.

“A few years ago the case law on how to claim, and how much could be claimed, was pretty undefined. However, the number of claims are now significantly coming through” he explains, noting that most of these losses do not relate to cyber security breaches.

He notes that while multiple compensation claims may be individually small, they are numerous and the legal fees associated with each are multiples of the actual compensatory sums. This could be storing up trouble for the future if underwriters are forced to remove a cover that has been traditionally expected by insureds.

“As the exposures go up, insurers may row back on the extent of cover, in which case people are going to find themselves uncovered for certain cyber events and certain privacy violations.”

“…That’s where the disputes will be – where people previously thought they were covered and they are not,” Allnutt warns.

In conclusion cyber is a young and immature class whose covers are evolving and are yet to be tested. (see Box below).

The above quartet shows the class brims with the possibility for forcible and potentially very costly accelerations into maturity. Many other as yet unidentified mismatches are undoubtedly lurking.

Let us hope this high flyer can reach a mature state without having to learn any expensive lessons.

Privacy and the evolution of cover

The sharpening focus on privacy around the world is one of the big drivers in the evolution of cyber cover, says Doyle.

“I think the natural evolution of the cyber policy has to be that it is at least split in half. When you think about it, how many policies exist that cover everything from first party costs, rectification and business interruption through to third party privacy, regulatory and liability exposure. Most even throw media liability in there for good measure. It is also effectively the same policy cover, whether you are a local hairdresser or a global telecommunications company. As the privacy and third party covers in the cyber policy continue to be triggered, with sizeable losses, the policy has to become two, maybe even three policies sold independently.”

The experience in the United States is similar, says Ian Stewart.

“In the US, the cost of privacy-related litigation is driven in large measure by federal and state statutes that allow private rights of action, and particularly consumer class actions. Not every data breach results in significant liability, if any. Where individuals’ personal information is compromised, however, the costs soar. When it comes to insuring these risks, it can now fairly be stated that the privacy tail wags the cyber dog”.

Elsewhere, the courts are driving the development of liability for privacy breaches.

“We expect Canadian courts and regulators will further develop the law to widen the scope of parties who are responsible for breaches of personal information,” says Karen Zimmer and Brianne Kingston of Alexander Holburn Beaudin and Lang in Vancouver.

“The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada has assumed jurisdiction to ensure that international service providers meet Canada’s statutory requirements related to safeguarding personal information where there is some connection to Canada.

“While Canadian courts have yet to hold an organisation vicariously liable for a data breach caused by a rogue employee, there are various cases on this issue proceeding through our courts.”

One involved a class action against an organisation for the actions of a rogue bank employee. “The court recognized that the doctrine of vicarious liability could potentially apply to hold the employer liable in circumstances where the employee had unsupervised access to customers’ private information, including having no monitoring system in place, thereby enhancing the risk of the rogue employee’s breach,” says Zimmer.

The above quartet shows the class brims with the possibility for forcible and potentially very costly accelerations into maturity. Many other as yet unidentified mismatches are undoubtedly lurking.

Let us hope this high flyer can reach a mature state without having to learn any expensive lessons.