The Aftermath of Brexit: Adjustment, Adaptation and Acceptance

Insurance and financial services were conspicuous by their absence from the last-minute deal to seal the departure of the UK from the European Union (EU), signed as COVID-constrained festivities were about to commence on Christmas Eve last year.

Slowly, out of the mists of political uncertainty, signs of what the aftermath of the Brexit break-up might mean for insurers in the UK and EU are beginning to emerge. They point to a sharper, faster divergence as the UK exercises its new-found freedom and the EU continues to strengthen its own regulatory regimes. This is something the UK must accept, says the newly-recognised EU Ambassador to the UK, João Vale de Almeida.

Speaking to journalists, he described how "three 'As' -- adjustment, adaptation and acceptance" sum up current EU-UK relations. Accepting that the UK is no longer a member of the EU is a process still in progress on both sides of the Channel: "We need to accept the new reality. Decisions have consequences, hence the need for adjustment and adaptation," he said.

Equivalence

In the run-up to the Brexit departure, there was much talk in the UK’s financial services sector about equivalence between the UK and EU regulatory regimes. This was always the fall-back position once it was clear that there was no hope of maintaining passporting and full access to the single market. It is turning out to be something of an illusion.

In the wake of the Christmas Eve deal, both sides agreed to produce a Memorandum of Understanding on Regulation by the end of March 2021, to pave the way for a new mode of co-operation between EU and UK financial regulators. Once signed, the first job of the Joint Forum it would set up would be to look at areas where the EU might grant equivalence, the UK having already recognised 17 areas of EU regulation as equivalent.

This process quickly fell into the political mire. By the end of March, all that was on the table was an outline agreement on the technical measures it might contain. As rows over the access of French trawlers to Channel Island waters and the procurement of vaccines gathered force, the agreement stalled. Even if deals on equivalence do eventually emerge, uncertainty will still haunt UK firms as, under current equivalence regimes, the EU has the power to withdraw access at just 30 days’ notice.

The UK insurance market has moved on

While some sectors of the UK’s financial services industry might still be fretting over equivalence, the UK insurance market has moved on, says Mathew Rutter, Insurance Advisory Partner at DAC Beachcroft in London.

“Equivalence is something of a red herring as UK-based firms have largely made their arrangements in the EU on the assumption that there would be no passporting and no equivalence. Even if the scope of the existing equivalence regime were to be expanded, the uncertainty created by equivalence being under constant review was too much of a risk, especially on claims.

“The other feature of equivalence is that you have to stay equivalent which means that you are then a rule-taker.”

Rule-taking has been a number one concern for the Association of British Insurers throughout the Brexit process, says Carol Hall, Head of European and International Affairs at the ABI:

“We have always said that we do not want to be a rule-taker and that we believe UK regulators should be able to act in a way that is appropriate for the UK. It still feels early days but Andrew Bailey [Governor of the Bank of England], John Glen [City Minister] and others are using the right terminology so it does feel that we have been heard on that front.

“We know that we have to keep close to the EU and have to adjust to looking at things from a third country perspective.”

Divergence

Joanne Finn, Partner and competition law specialist in DAC Beachcroft’s Dublin office, said no-one should expect any major moves on equivalence from the EU side.

“The pressure to get something agreed has gone. Where is the economic incentive for the EU regulators to give equivalence? They have a regime that the EU27 are signed up to, based on 30 years of hard-won compromise. Changing the course of that cruise liner to follow any new course the UK might want to follow is not a priority.”

Finn adds that with the focus now on divergence, the EU will be watching the UK carefully as it shapes its own financial services regulation: “UK politicians have sent out a signal that we should expect divergence but the complex practicality of divergence if it implies a dual regime is not likely to appeal to UK insurers operating on an international scale.”

The signal from the UK government has been received loud and clear by the European Commission, prompting an unequivocal warning from Mairead McGuinness, the Commissioner for Financial Services, in a recent TV interview:

“We have heard words like deregulation. We know that Brexit was about moving away from what Europe has done across all sectors and possibly including the financial sector. We do recall the past and light-touch regulation in financial services, and it did no one any favours.”

Hall was keen to stress that Europe should still expect the UK to set high standards:

“When it comes to conduct regulation, the UK has always been seen as setting the standards and going above the minimum harmonisation requirements.”

Rutter said he does not expect drastic changes, echoing Hall’s reassurance:

“I suspect it will be incremental rather than a big bang. It will be more about fine-tuning. It is not as if the UK has been a reluctant regulator in the past.”

That incremental divergence started at the beginning of June 2021 when the UK Treasury announced that it had extended exemptions around product disclosure for UCITS funds (Undertakings for the Collective Investment in Transferable Securities), required under the Packaged Retail Investment and Insurance-based Products Regulation (PRIIPs) for five years, with the promise of legislation before the exemption expires.

UK firms set up in the EU

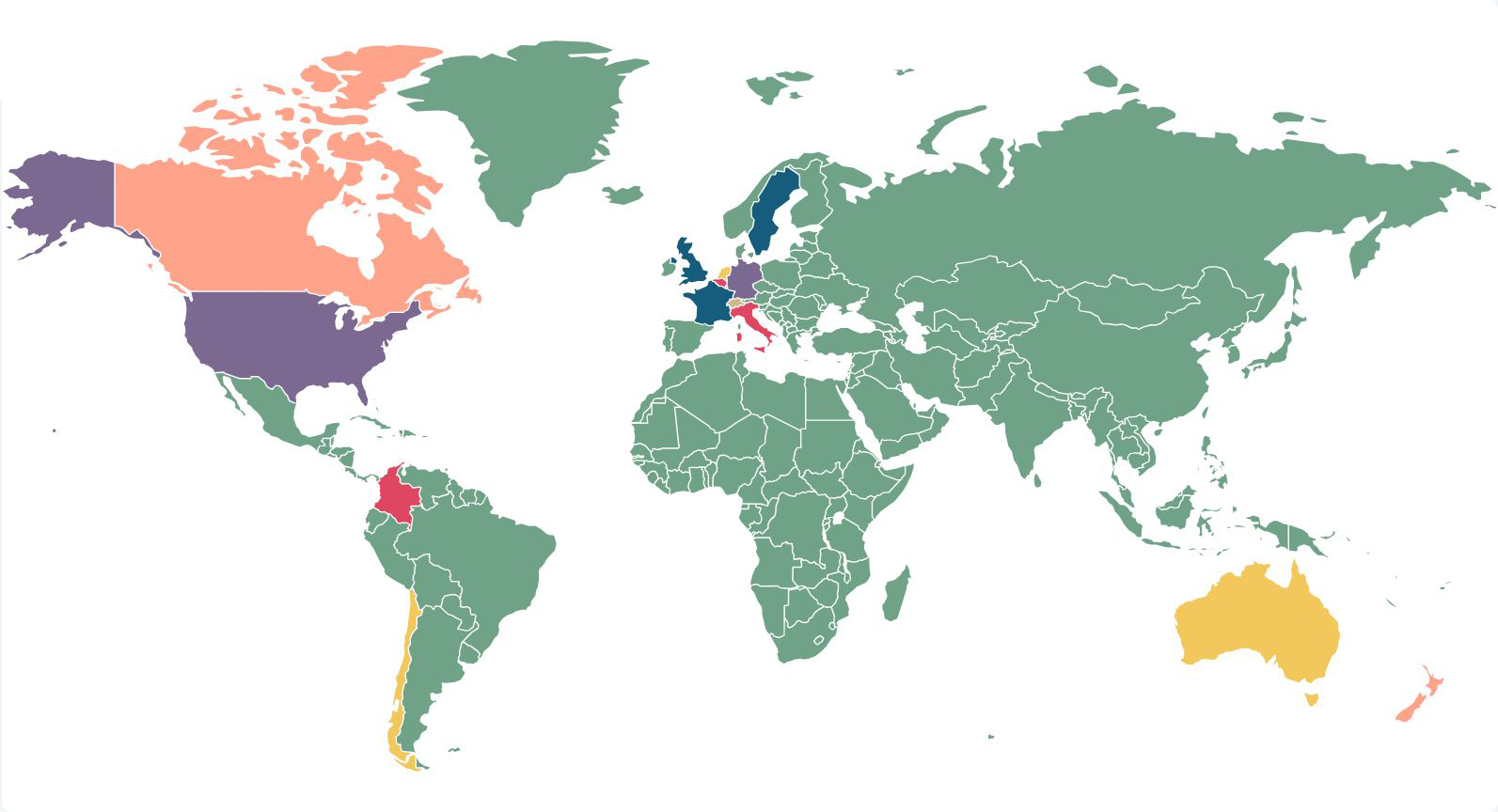

While the Brexit talks dragged on, UK insurers and brokers made their moves, re-domiciling business to the EU so they can continue to serve EU clients. Ireland has been one of the big winners in the process, with Luxembourg, Frankfurt and Paris also attracting some UK firms. Lloyd’s chose Brussels as the base for its new European office but few market players have followed them there.

National regulators have been rigorous in their approval processes, following the lead of the pan-European regulator EIOPA (European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority). Ireland was an obvious choice for many firms but the Central Bank of Ireland set the bar high, says Elaine Davis, Senior Associate -Barrister in DAC Beachcroft’s Dublin office.

“The Central Bank has been very clear in its communications to the market and to those firms looking to become authorised here post-Brexit, in particular that it would not accept firms effectively being run from outside the jurisdiction. The Central Bank has insisted that management and key functions are based in Ireland. It has also been verifying that the extent of outsourcing arrangements does not result in the firm becoming an ‘empty shell’.”

Having jumped through these regulatory hoops in Dublin and elsewhere, UK firms cannot expect life to be plain-sailing as changes in European regulation are already looming large, increasing the divergence from the UK still further.

There is pressure from EIOPA on national regulators to be more consistent and rigorous in their enforcement. This is already being felt in France following the failure of several specialist construction insurers, says Vladimir Rostan d’Ancezune, Partner in DAC Beachcroft’s Paris office.

“We have a pretty good supervisory and regulatory framework but there are questions about how individual local regulators co-operate on enforcement. It is often a question of time and resource for some of the smaller regulators.”

EIOPA’s spotlight is almost bound to fall on UK entities that have re-domiciled business to the EU in order to maintain passporting rights across the 27 Member States, says Bastian Finkel, Partner at BLD Bach Langheid Dallmayr in Cologne.

“UK insurers have set up their entities in Europe so they can continue selling policies but they still have a lot of their internal services provided from London. Previously, this was fine with European regulators. Now, the question is whether the European authorities will still accept the handling of key insurance functions from London. This will be an important issue because the London insurers will only want to have those functions in one place. It could become a key political question.”

His colleague and Partner at BLD, Dr Alexander Beyer, says he senses that EIOPA is straining to extend its remit.

“They are more and more involved in the daily business of regulation. They look for whether the regulations they make on a European basis are enforced by the national regulators and that interaction is getting more intense. I think we are still at the beginning of a process.”

Commission disclosure threat

Also high up on the European Commission’s and EIOPA’s agendas is a review of the Insurance Distribution Directive as part of a greater emphasis on consumer protection. This could include new rules on transparency around commission or even controls on when and how much commission can be paid.

This would not be welcomed by intermediaries in Germany, says Beyer.

“They will look again at commission and conflict of interest rules and with some regulators, including Germany, pushing fee-based sales, there are concerns about how people would get access to advice. This is an area where we can learn from the UK,” a reference to the Retail Distribution Review that imposed strict rules limiting commission payments on long-term savings products.

The far-reaching Solvency II rules are up for review too with a sharp stand-off between insurers represented by Insurance Europe and the regulator, EIOPA, over the weighting given to certain long-term investments such as those in infrastructure. It is seen as a not entirely welcome legacy of British membership in some quarters, says Vladimir Rostan d’Ancezune: “The review of Solvency II is something that was wanted and led by the British and now they are no longer part of it.”

This has the potential to add a further dimension to divergence as the UK regulator, the Prudential Regulation Authority, has struck a much more sympathetic stance when it comes to how long-term investments are treated under the matching adjustment regime.

Keeping score

The divergence scorecard is already lengthening and that is just for insurance specific regulation. Also looming are concerns over data protection and artificial intelligence (see Box: Mind that data). The UK’s relationship with the EU when it comes to the regulatory regime increasingly feels like the line from the Eagles’ hit Hotel California: “You can check out anytime you like, but you can never leave.”

Mind that data

The EU is very sensitive about data protection and that sensitivity will ripple across the UK. It could be exacerbated by the anticipated introduction of an Artificial Intelligence (AI) Directive by the EU.

“The key issue for many is where data is stored,” says Vladimir Rostan d’Ancezune. “Some do not want it stored outside Continental Europe. The UK is not the US [where data protection laws are perceived as being weaker] but it does depend on how the UK continues to ensure protection for personal data and how that evolves over the next three, four, five years.”

In Rutter’s view: “If customer data is going to be held elsewhere than in the UK then the place we would be happiest with is the EU where regulation is much tighter than countries such as the USA and India where it is more lax.”

This leads to the conclusion that the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), introduced just a few years ago, needs to be mutually respected.

“Leaving GDPR where it is will help reassure everyone,” says Beyer. This does not mean that the UK and EU might not gradually part company over how they are implemented, he says.

“There are different readings of the same words. Previously, we would have all waited for the European courts to decide what they mean. Now, there is the risk that different courts will view them differently and the implementation and understanding of the GDPR could diverge.”

At the end of August, the UK government said it was examining GDPR. The word of the culture secretary, Oliver Dowden, raised the spectre of divergence: “Now we have left the EU, I’m determined to seize the opportunity by developing a world-leading data policy that will deliver a Brexit dividend for individuals and businesses.”

This could leave UK insurers and brokers having to comply with multiple regimes, warns Finn: “If the UK chooses to diverge from EU rules, it will test the appetite of businesses to operate dual regimes. Practically speaking, insurers may not like the duplication and increased costs that will bring.”

On the regulatory horizon is a raft of other technology regulation issues that will test the boundaries of divergence.

The proposed AI Regulation (published on 21 April 2021) would apply to all sectors, including financial services. Similar to the GDPR, it would cover providers and users of AI systems that are established in the UK, to the extent the output produced by those systems is used in the EU. Some of the proposals are specific to financial services.

AI systems used to evaluate creditworthiness or establish credit scores would be subject to the mandatory requirements for “high risk” AI, including the need for human oversight.

Transparency requirements, such as informing individuals they are interacting with an AI system, would also apply to the use of chatbots.

The requirements in the proposed AI Regulation would not cover all AI use in the financial services sector, but the proposals encourage organisations to develop and adopt voluntary codes of conduct which incorporate the mandatory requirements for “high risk” AI and apply such requirements to all uses of AI. It is expected that companies operating in multiple jurisdictions will largely align to the new rules to ensure world-wide compliance.

Wider alignment of rules would be the best way forward, agrees Rutter.

“There is no particular incentive for divergence in this area. There would be definite advantages in consistency unless there is some aspect of the EU regulation that is just off the scale in terms of its impact.”

New agreements on Gibraltar

Gibraltar remains a sensitive issue in the post-Brexit world, as all future agreements on the relationship between the UK and the EU will only apply to Gibraltar if Spain agrees not to exercise its veto.

There has been more positive news on that front for the many UK insurers and MGAs based there, advises Marisol Lana, Senior Associate in DAC Beachcroft’s Madrid office.

“On 31 December 2020, the UK and Spain reached an “in principle agreement” for Gibraltar to join the EU’s Schengen Area and in March an International Tax Co-operation agreement between the UK and Spain – which was signed two years ago – came into force. This will make Spain take Gibraltar off its “blacklist” of tax havens where it has been since 1991. The aim of this treaty is to ensure that Gibraltar applies EU-equivalent legislation in terms of tax transparency and the fight against money laundering, addressing Spain’s long running grievances over tax evasion.”

This follows an agreement between Gibraltar and the UK government to maintain reciprocal access after Brexit, without which the UK motor market would have faced severe disruption with over a quarter of capacity currently provided by entities based in Gibraltar. This agreement was subsequently given further force in the Financial Services Act 2021 which created the Gibraltar Authorisation Regime to ensure continuity and regulatory alignment.

Competitiveness could come to the fore

One post-Brexit hope across the UK financial services sector is that regulators will take the competitive position of the sector into account when framing new regulations. Several attempts to enshrine this as a regulatory objective were made during the recent passage of the Financial Services Act through Parliament but were rejected by the government.

There was better news on this front when The Taskforce on Innovation, Growth and Regulatory Reform published its report in June this year. This says priority should be given to promoting innovation and competitiveness through regulatory reform, although this refers to all sectors of the economy, not just financial services. The proposals will now be subject to consultation by a new Brexit Opportunities Unit headed up by Lord Frost.

“The key thing it highlights is the need for the FCA, as well as other regulators, to have competition and innovation objectives rather than taking a ‘better safe than sorry’ approach. But, of course, that will only happen if politicians also accept that regulators should not be expected to operate a zero-failure regime”, says Rutter.