The #metoo movement: changing the workplace forever

Movements such as #MeToo and #TimesUp have meant harassment claims have extended beyond employment practices liability into D&O liability insurance and both governments and employers are considering significant changes.

When American actress Alyssa Milano encouraged survivors of sexual harassment to post #MeToo as their status back in October 2017, few could have predicted the impact this single tweet would have. Although the phrase had been around since 2006, the power of social media meant it quickly went viral, with far-reaching repercussions.

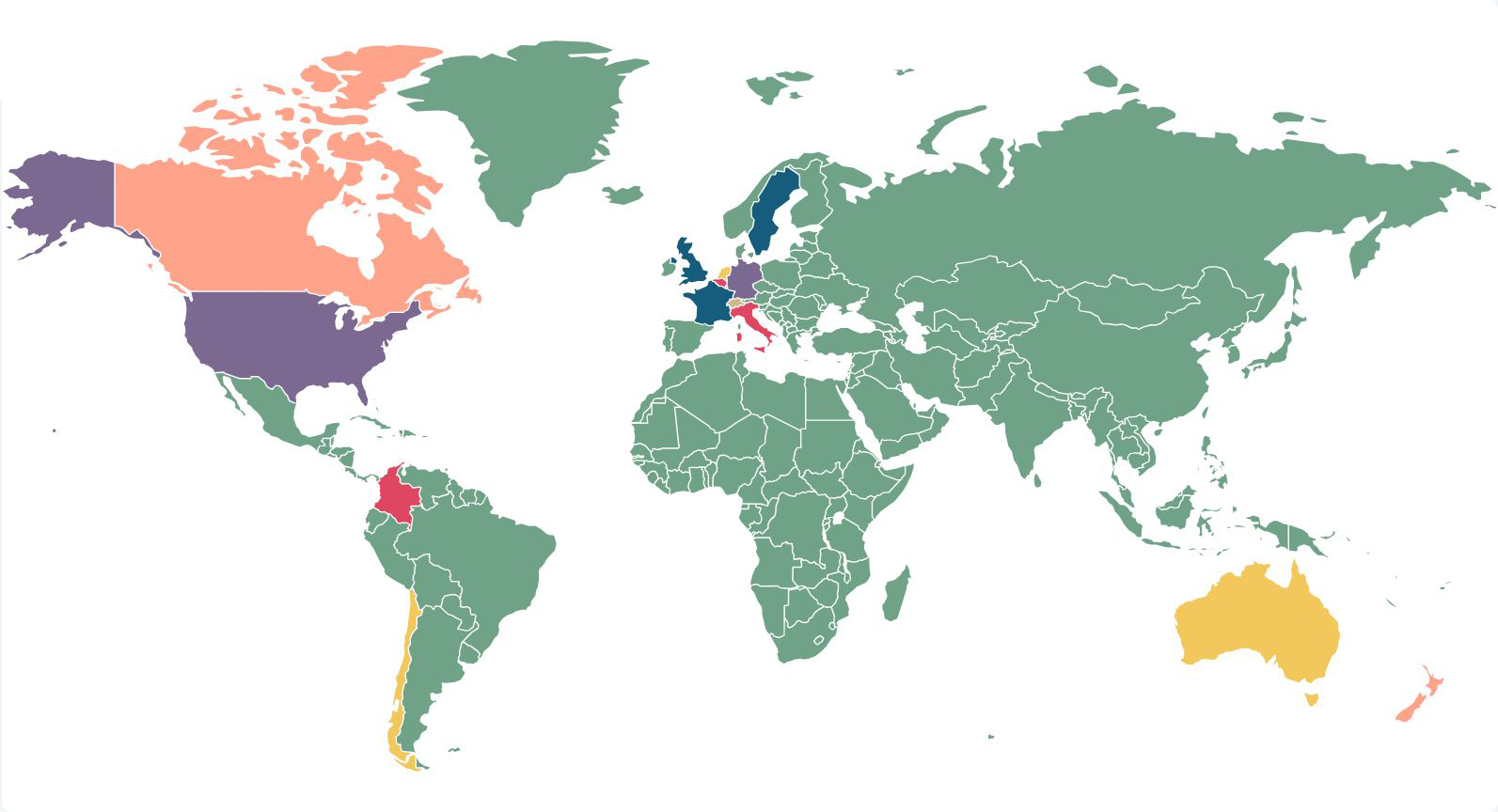

Just a week after that initial tweet, #MeToo had been tweeted more than 1.7 million times by people in 85 countries. On Facebook, 4.7 million users around the world had posted in excess of 12 million posts, comments and reactions.

Extraordinary reaction

Raising the profile of sexual harassment and giving a voice to many who had not previously felt able to speak has shaken the world. “It’s been extraordinary,” says Ricki Roer, Regional Managing Partner at Legalign firm Wilson Elser in New York and founding Chair of its National Employment & Labor litigation practice. “Claims of sexual harassment have increased dramatically since 2017. We haven’t seen anything on this scale since allegations of sexual harassment were brought against Clarence Thomas in 1991.”

This uptick is shown in figures from the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. At the end of the fiscal year ending 30 September 2018, it recovered almost US$70 million from employers for survivors of sexual harassment, up from US$47.5 million the previous year.

It’s a similar picture in other countries too. In Australia, where sexual harassment cases can be brought at a federal or state level, the numbers are up in nearly every jurisdiction. In the year to September 2018, New South Wales saw the largest increase, with claims up by 39%, while claims in the federal arena rose by 19%.

In December 2018, a Bauer Media poll reported that 82% of New Zealand women have experienced either sexual violence or sexual harassment. These numbers do not appear to be reflected in claim volumes, but New Zealand only started collecting data on sexual harassment in the workplace in July 2018. A recent investigation suggests that sexual harassment complaints in the public sector have doubled between 2015 and 2018 and with the current environment more supportive of disclosure, it is expected that claim numbers will rise.

Ireland has also seen an increase in cases, with the 200 gender-related statutory claims it saw in 2016 rising steadily to 350 in 2017 and 318 in 2018. David Kennedy, Senior Associate at DAC Beachcroft in Dublin, says that while there was a spike in claims around the time of the #MeToo tweet, he believes other factors are affecting the figures. “There have been some high-profile cases in Ireland,” he explains. “As it has become so newsworthy, it may be that employers are more prepared to settle than they were before.”

The same is being seen in the UK. The introduction of tribunal fees in 2013 caused more than an 80% decline in claims but, following their abolition in 2017, the 2018 employment tribunal statistics showed that at certain points the number of sex discrimination claims was reaching the levels seen pre-2013. Louise Bloomfield, Partner at DAC Beachcroft in Leeds and Head of its Employment Practices Liability team, also notes that there has been a 56% increase in UK pregnancy discrimination claims, commenting that: “Employees appear to be much more confident in challenging what is seen as unacceptable behaviour in the workplace.”

Even where #MeToo has had less of an effect, societies are finding themselves grappling with the same issues. Germany is a good example of this, as Bastian Finkel, Partner at Legalign firm BLD, explains: “The #MeToo movement isn’t as big in Germany, but equal treatment has been a hot political, social and moral issue for the last few years. The ‘No Means No’ campaign has been running here for around five years.”

Under pressure

Regardless of which drivers are at play, expectations are that the number of claims will continue to rise according to Raisa Conchin, Partner at Legalign firm Wotton + Kearney in Brisbane. “These types of claims are still severely under-reported,” she says, pointing to research released by the Australian Human Rights Commission in September 2018. This suggests that, although 71% of Australians have been sexually harassed at some point in their lives, just 17% of those who experienced sexual harassment at work in the last five years made a formal report or complaint.

Neither is the pressure likely to come off. As well as empowering more people to launch claims, the #MeToo movement has also resulted in the creation of organisations such as Time’s Up in the US and NOW in Australia.

Sharing the goal of stamping out sexual harassment in the workplace, they also raise money to help individuals access legal support and counselling. For instance, within just two months, Time’s Up had raised more than US$21 million and attracted nearly 800 lawyers prepared to offer their services on a voluntary basis.

Money is flowing from other sources as well. In New Zealand, the crowdfunding platform Give a Little, raised more than NZ$55,000 to defend a defamation claim by the country’s Conservative Party founder Colin Craig against his former press secretary Rachel MacGregor. In a separate claim, Mr Craig was found to have sexually harassed Ms McGregor on multiple occasions. His defamation claim appears to have no prospect of success, but it may indicate a worrying trend of wealthy perpetrators using defamation actions to discourage or further persecute harassment victims.

Public focus has also expanded to include other groups that have suffered discrimination. In the US, the #UsToo movement was created to seek equality for individuals who had suffered racial discrimination. In Germany, football star Mesut Özil sparked the launch of the #MeTwo campaign (based on his having both a German and a Turkish identity) when he resigned from the national team citing racism and disrespect.

In this climate, Roer says that employers need to be aware about all aspects of the work environment. “It’s not just a sexual harassment issue,” she says. “Disparate treatment undermines the workplace. Social media can allow these issues to go viral, potentially undermining recruitment as well as increasing litigation exposure.” Government action

Given the scale of the outcry, many governments have been forced to develop responses to the issue of sexual harassment. While some of this is still at the information gathering stage, others are already a long way down the path to introducing more robust legislation to protect individuals in the workplace.

This is the case in the US. Laws have been passed in states such as California and New York requiring employers to implement anti-harassment training and the Bringing an End to Harassment by Enhancing Accountability and Rejecting Discrimination in the Workplace Act (more commonly referred to as the BE HEARD in the Workplace Act) is set to overhaul harassment laws at a federal level. Roer says it will replace legislation that has been in place since 1964. “It will extend rights to a much broader class of people and make it easier to bring a case,” she explains.

Anticipated changes include the potential extension of health and safety legislation to include a specific duty to protect from sexual harassment. By making it a regulatory issue, it would take some of the pressure off employees who don’t want to go to court and would also mean both quasi-criminal fines for businesses and potentially jail sentences for officers who fail to protect their employees

Changing attitudes

While some countries’ politicians are grappling with new legislation to combat sexual harassment in the workplace, others are finding that it feeds into a broader discussion on equality. The aim of the Irish Government’s National Strategy for Women and Girls 2017-2020 is to create a better society for all by promoting action on women’s equality.

For Kennedy, it is part of a broader shift in attitudes in Ireland. To illustrate this, he points to changes including the overturning of the abortion ban, the introduction of statutory paternity leave and the Gender Pay Gap Bill. “Ireland is at the forefront in protecting employees from discrimination, with powerful statutory remedies in place,” he says. “But #MeToo has definitely provided an impetus for further change.”

In some countries, the movement is even forcing change to the language. This is the case in Germany, where gender is an integral part of the language. Unsurprisingly, given the current focus on equality, this bias towards masculine genders is causing plenty of consternation. “It has triggered a huge political debate around whether the German language represents today’s world,” explains Christina Eckes, Partner at Legalign firm BLD. “It has made everyone stop and think about how you phrase sentences. Do we want our language to be in line with our position on diversity?”

Workplace shift

Employers are also finding themselves making changes to protect their employees from sexual harassment and discrimination in the workplace.

For some – such as the US states of California and New York – the requirement to take a more proactive approach to protecting employees has been mandated, with laws passed requiring employers to provide anti-harassment training and awareness. Others say it is more of a cultural shift. “We are seeing enhanced workplace policies and more training being put in place,” says Kennedy. “The focus on sexual harassment means that more people will come forward, but these changes should help to reduce risk by improving working conditions. We have come a long way from the culture of silence in the workplace.”

There is also considerable pressure on employers to make changes. As an example, after demands from employees and unions for better protection from sexual harassment, the American Hotel and Lodging Association, which includes major hotel chains including Hilton Worldwide and Marriott International, agreed to install safety devices such as panic buttons by 2020.

The thorny issue of non-disclosure and confidentiality clauses is also being explored in some countries. In particular, as part of her National Inquiry into Sexual Harassment in Australian Workplaces, the Commissioner has called on employers to voluntarily waive confidentiality clauses to encourage more submissions. As a result, 13 major employers have agreed to this on a limited basis. Conchin says this is meaningful. “It’s a reflection of the support this issue has in Australia,” she says. “That this is happening on a voluntary basis means that employers recognise the importance of the inquiry, potentially even against their own interests.”

Insurance response

Putting robust policies in place to prevent sexual harassment and other forms of discrimination is a positive step, but the rise in both awareness and the number of claims means that #MeToo is a significant insurance industry issue.

Employment practices liability policies offer cover for sexual harassment and discrimination claims brought against the organisation. Both Bloomfield and Kennedy have seen more litigation in this area in the UK and Ireland, with quantum rising. “More allegations of mental health injuries are being made in this area,” says Kennedy. “Where an employee claims they have suffered psychological harm such as depression or post-traumatic stress disorder, it can be a difficult case to defend. Courts will often accept the medical evidence, even where a medico-legal doctor has only spent a short time assessing the claimant.” As a result, while awards in Ireland have typically been around two years’ salary, some recent cases have been as much as four.

Bloomfield notes that in the UK, damages and also settlement expectations are increasing, alongside an increase to injury to feelings awards up to a maximum of £44,000 and employment tribunals also being able to award up to £20,000 as aggravated damages.

The impact of these types of claim means that, in some countries, they’ve moved beyond employment practices liability and on to shareholders’ claims, triggering directors’ and officers’ insurance. This is particularly the case where the board has failed to act on sexual harassment allegations or is shown to have turned a blind eye.

Other insurance policies are also being affected. Following a review into sexual harassment at New Zealand law firm Russell McVeagh, and evidence that nearly one third of female lawyers in New Zealand have experienced harassment, the New Zealand Law Society increased its attention on the issue. Its Standards Committee recently imposed a professional disciplinary fine of NZ$12,500 on a law firm partner for inappropriate behaviour at work social functions. This was significant, because the Standards Committee found he was providing regulated services at the time, which creates new exposures for professional indemnity insurers.

More positively, the increased focus on sexual harassment also appears to be driving take-up of insurance. Conchin explains: “We are seeing more employers taking out employment practices liability cover on a standalone basis or as a bolt-on to management liability cover. Where an organisation has an insurance broker, it’s rapidly becoming the norm to have this cover.”

Conchin is also heartened by the actions of insurers in this space. Many provide educational material to brokers and employers to help them ensure the right procedures such as training and policies are in place to prevent sexual harassment in the workplace. “Five years ago, this wasn’t really on the agenda, but we now have insurers getting behind a campaign to raise awareness and lower risk,” she adds. “It’s very positive.”