From fossil fuels to renewables: the challenge of climate change

While artificial intelligence and Brexit may transform commerce and society, it is climate change that will irrevocably alter the world. Facing up to the impact of climate change, especially carbon emissions from fossil fuels, is now top of the agenda for many supra-national bodies such as the United Nations, the European Union and the World Bank. Climate change activists are no longer on the fringes but are listened to by these organisations, whether that be campaign groups such as Unfriend Coal or the Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg.

The insurance industry has now been dragged centre stage in responding to the challenge of climate change. This goes far beyond the need to meet claims from the natural catastrophes now attributed to climate change, although this is a major issue for regulators (see paragraph below: Regulators vigilant on climate change impacts). The huge losses of recent years have hit global insurers and the Lloyd’s market very hard and demand a re-assessment of risks, increases in premiums and investment in claims handling capabilities. That is a traditional role and response for the insurance industry.

However, the climate change debate and the agenda around sustainable finance takes the industry into uncharted territory. It is pushing insurers to respond to a political agenda by shunning fossil fuels as underwriters and investors. It also brings a new range of risks to the table as the renewable energy sector expands rapidly.

The role of the insurance industry

Top of the hit list for the campaigners is coal. The pressure group Unfriend Coal has the ear of the United Nations and the European Union. It is uncompromising in its belief in the central role of the insurance industry in driving towards its target of zero coal consumption by 2050, a modest ambition compared to some other climate change campaigners’ demands.

“Insurance companies are in a unique position to accelerate the transition to a low-carbon economy. As risk managers they play a silent but essential role in deciding which types of project can be built and operated in a modern society. Without their insurance, almost no new coal mines and power plants can be built, and most existing projects will have to be phased out.

With assets of approximately US$31 trillion, insurers are also the second largest group of institutional investors after pension funds. Reports commissioned by Ceres (a sustainability non-profit organisation) and Unfriend Coal have found that the largest US and European insurers have invested close to US$600 billion in fossil fuels,” says Unfriend Coal.

The campaign also points to the industry having a vested interest in ending coal-fired energy production:

“Insurance companies cover a large part of the increasing damages caused by ever more serious hurricanes, wildfires, floods and droughts. They have access to the world’s best climate science and have warned about climate risks since the 1970s. Continuing to prop up the coal sector is incompatible with their fundamental mission to protect us from catastrophic risk.”

“Their view is that if a coal-fired power station cannot get insurance then it can’t operate,” says Toby Vallance, Partner at DAC Beachcroft in London.

Several large insurance groups have responded to the pressure to limit and eventually withdraw from underwriting the extraction of coal and coal-based energy production, including AXA, Zurich, Allianz, Generali, QBE and most recently Chubb. At the end of 2018, 19 major insurance groups had also announced they would stop investing in coal.

This raises several interesting challenges for the insurance industry, and is not without its controversy and risks.

Divestment

The divestment argument has divided opinion with the leading research body, the Geneva Association, urging caution, according to its Director of Extreme Events & Climate Risk, Maryam Golnaraghi:

“A rising number of Chief Investment Officers are looking into opportunities for investing in green and climate-neutral assets, but they caution against divesting too suddenly from fossils fuels. This is because the biggest financial force in developing renewable energy is the fossil fuel companies as that is their exit strategy from carbon. Divesting too quickly could essentially be choking funding for investing in green technology.”

This concern was also raised at a recent European Commission conference on the progress towards sustainable finance when Hiro Mizuno, the head of Japan’s public sector pension scheme, the US$1.4 trillion Government Pension Investment Fund, said that: “Divestment means that we transfer ownership from the responsible investor to the less responsible investor; that's why we have a policy of no divestment.”

Similar concerns surround the withdrawal of underwriting capacity, says Carl Pernicone, Attorney at Law at Legalign firm Wilson Elser in New York: “Fossil fuels will still be needed as a back-up even after renewable capacity increases. What do you do when the sun doesn’t shine and the wind doesn’t blow? You can reduce reliance on it but can you get rid of it altogether?”

While it is unlikely we will be able to get rid of fossil fuels in the near to mid-term, growth in the likes of tidal energy and energy storage technologies may in time enable renewable energy to replace fossil fuels.

What cover will be available

What does the withdrawal of major insurers from underwriting coal mean for those businesses still needing cover?

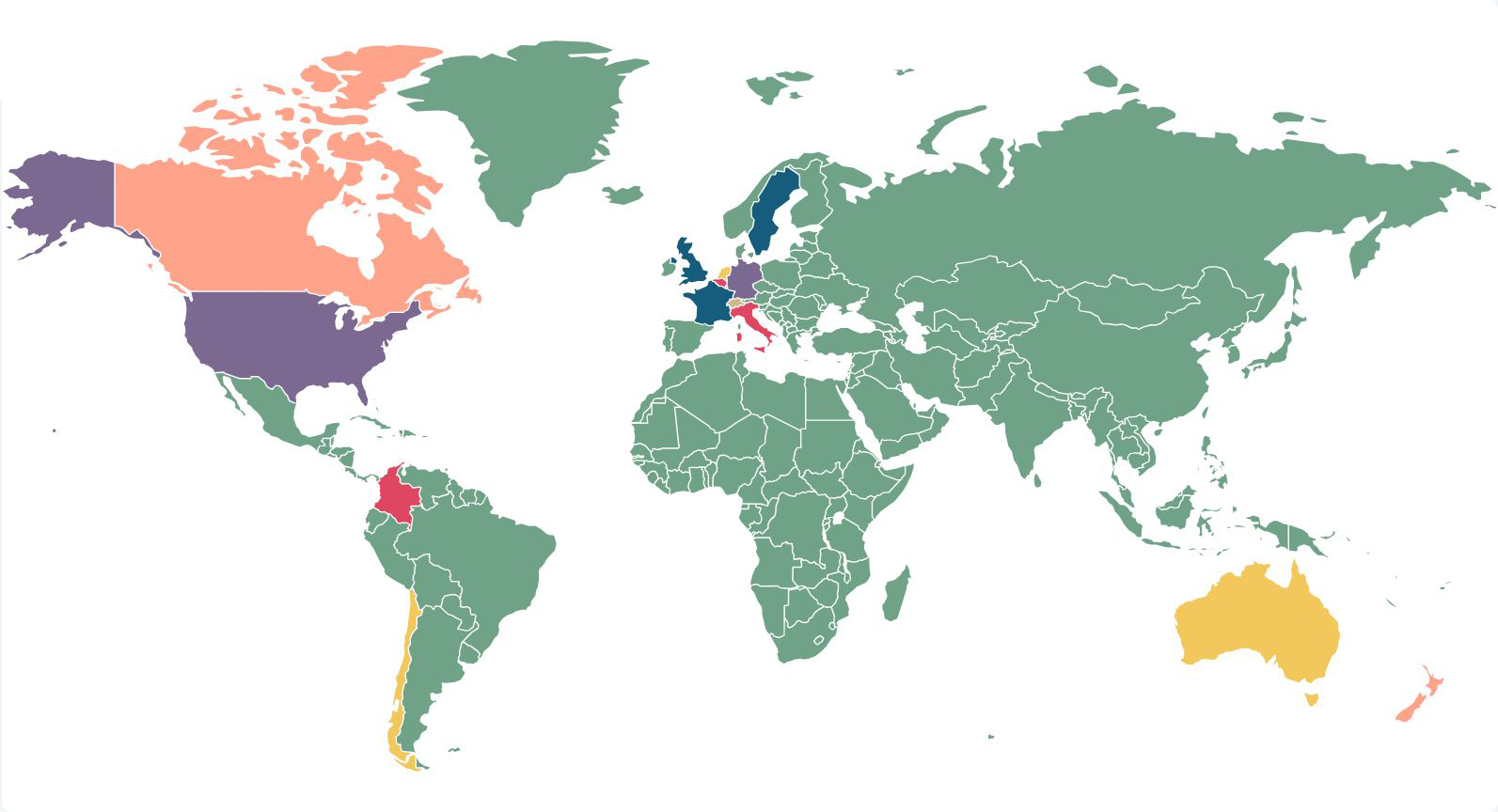

“They will probably have to pay more for it, especially in Europe,” says Duncan Strachan, Partner at DAC Beachcroft in London. “It is a different picture in North America. The fossil fuel industry in North America is huge, as it is in China and with oil and other natural resources in Latin America. There is little prospect in the current political climate, for instance, that the Venezuelans are not going to insure the oil industry.”

“I don’t think you can totally move away,” says Pernicone. “They will have to insure somewhere. They may have to self-insure or form captives. If they clean up their act perhaps some of the insurance groups will come back.”

According to Hamish Roberts, Chief Executive Officer of the Power Division at JLT Specialty, writing in a US publication, brokers are not experiencing any problems finding capacity for fossil fuel risks: “As a broker we are still able to arrange company programmes for our clients despite this public and noticeable withdrawal of capacity. Yes, more insurers and reinsurers are stopping or limiting their insurance support for coal, but an ingenious broker will always be able to devise risk-transfer solutions.”

Potential claims

Remaining active as an underwriter of fossil fuel-dependent businesses will not be without its risks, says Strachan.

“The operators are going to face increasing claims for environmental damage. Traditional types of cover will not extend to that type of liability. There is a big gap for the insurance industry to offer cover for the sort of awards we are likely to see,” he adds, citing a recent award of US$10million in Ecuador for damage to the local community by an oil refinery.

Elsewhere in Latin America, governments are making significant moves to hold firms responsible for pollution, says Liliana Calvo Rojas, a Director at DAC Beachcroft in Mexico.

“In 2012, Mexico passed the Climate Change General Law in order to promote education, research, development and mitigation of climate change.

“We now have a Federal Protection Authority for environmental purposes, which carries out inspection and surveillance actions for the entities required to provide reports due to the emission of gases. In the case of an imminent risk, they could be subject to a sanction in accordance with environmental laws, with the directors being exposed to administrative sanctions and lawsuits.”

In Peru there is legislation in place that requires liability policies to respond to claims for environmental damage.

One case from Peru has found its way into the European courts. A Peruvian farmer has taken a German firm to court to recover the cost of protecting his home town from damage caused by a melting glacier. The farmer is arguing that carbon dioxide emitted by factories owned by RWE had been a major contributor to global warming and the consequent melting of the glacier. The case was originally rejected by the lower court in Germany but has been ruled admissible. This will be watched very carefully across Latin America, says Calvo Rojas, and could provoke many more claims.

Governments across Europe have passed or are in the process of passing similar laws, with France leading the way in requiring firms to report on their carbon emissions. It is not hard to see the regulatory and reporting burden on energy producers increasing significantly in the next few years.

“In theory, there should be capacity to cope with this but that cannot be guaranteed. If these actions become commonplace, say if there is an action from a large urban area and courts around the world follow that, then there might be doubt over the capacity available,” warns Vallance.

Renewable energy - new risksAs they move away from fossil fuel risks, insurers are expected to be supportive of the rapidly developing renewable energy sector, such as onshore and offshore wind farms and solar energy installations. This also presents challenges, says Bastian Finkel, Partner at Legalign firm BLD in Germany:

“If insurers change from covering old energy types to newer energy types, they have a whole new range of risks on their books. They will then have risks of which they do not have much experience.

This is not just about the physical risks but also about the increased connectivity and inter-dependence of different producers and firms in the production and distribution supply chain says Finkel’s colleague, Partner Christina Eckes: “Insurers will also have to look at how the technology moves together with blockchain and data risk. These issues about how they communicate are very new.”

In her view, this is a political issue as well: “The discussion is all about the new infrastructure and insurers are putting risks on their books that they might not be able to assess in a way they could in the past.”

For Denise Eastlake, Senior Associate at DAC Beachcroft in London, rapid development of the technology inevitably poses a challenge for insurers, however, there is already capability in the market:

“There are certainly lots of new entrants to the market and the technology is constantly evolving. However, the first UK wind turbine came online in 1991 so there is already some considerable expertise in the market. Insurers can also draw on their knowledge from underwriting and handling claims in other areas of the energy sector and dealing generally with engineering risks.

“The impact is not only in relation to the insureds that construct and operate renewable energy plants, but extends to all those engaged to service, monitor and repair these plants. You may have a relatively small engineering firm facing large business interruption claims where defective works have caused an interruption of supply.”

One response to this problem has been to put broader policies in place at the project planning stage, says Eastlake: “Project policies are getting wider and wider as the banks and investors insist on these risks being addressed.”

The risks to which some renewable energy installations are exposed are not well understood, says Vallance: “Many of them have a vulnerability to extreme weather events, perhaps related to climate change.”

This is another issue that needs to be addressed early in a project, says Eastlake: “It is hard to say whether the design, materials and build are right as windspeeds, for instance, are often unknown. It is essential that engineers and underwriters delve into these risks. Smart underwriting comes into its own and pays off in the long-term.”

“In Australia, we have seen rapid investment in renewable infrastructure,” says Adam Chylek, Head of Property and Energy at Legalign firm Wotton + Kearney in Sydney. “Many of the issues that we are seeing arise from the perceived imbalance between the almost unfettered appetite to develop the assets, against the high risks – associated with weather, defects in design and workmanship – which lead to significant claims. Many component assets are designed or manufactured offshore, and regularly have a critical operational impact; when they fail there is a chance of a significant total loss.

“We are also seeing contractors being asked to agree to unworkable warranties in areas around foundations, ground stability and operational life, which often far exceed ordinary contractual terms and the capacity of responsive insurance policies.”

It is important to understand what can go wrong with renewable energy installations, says Ryan Williams, Attorney at Law at Legalign firm Wilson Elser in Denver:

“We need to look at what renewable energy has in common with other energy production industries as well as trying to imagine what is different about the renewable energy businesses. We have had to consider what end-users might expect and what the potential claims might be. With renewables it is more about the economic impact of something going wrong than the environmental impact.”

The insurance industry, reluctantly or willingly, is a key player as the world embarks on its journey from fossil fuels to renewables and is going to have to respond to many new challenges along the way.

Regulators vigilant on climate change impacts

The Bank of England has led the way among global regulators in warning of the risks climate change poses to the insurance industry. Through the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) it has released a series of supervisory statements urging insurers to identify and manage financial risks relating to climate change, the most recent being in April 2019.

The PRA expects insurers to have plans for how best to approach climate change within their current policies, especially meeting massive claims from the growing number of severe natural catastrophes. It wants the industry to look at how it can address the risks posed by this issue.

It has also warned that insurance companies could face a significant downgrade on their investments in fossil fuel companies if governmental pressure accelerates the move away from fossil fuels.